What Does Accountability Mean for the Public Transportation Sector?

By Rashidi Barnes | 3/7/2024

RASHIDI BARNES

Chief Executive Officer

Eastern Contra Costa Transit Authority / Tri Delta Transit

Antioch, CA

As some public transit agencies nationwide face fiscal cliffs, we find ourselves pitted against a familiar challenge: accountability measures. For decades, key performance indicators (KPIs) determined whether or not an agency was efficient and practical. KPIs, like on-time performance and how many passengers per hour we transported, were the accountability metrics that each agency focused on. As we crawl out of the pandemic ridership devastation, advocates, stakeholders, and politicians are asking for new accountability measures if public transit agencies want future operational funding to sustain their current service offerings and avoid the fiscal cliff.

I agree that public transit agencies are stewards of public funds. I also concede that the past KPIs needed to be updated because they did not tell the real story about service efficiency. Putting that aside, I ask: were most agencies not accountable in the past if they met the industry provided KPIs? If not, then what does accountability mean today for the public transportation sector? We will likely receive ten different answers if we ask ten policymakers and/or transit advocates what public transit accountability may mean to them. Maybe even a few that seem to contradict.

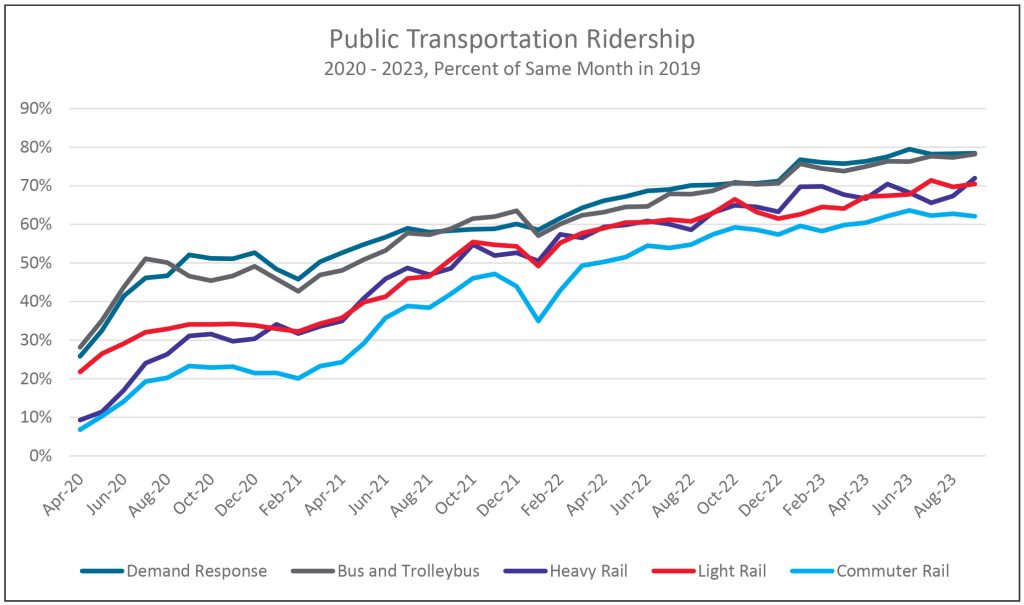

A recent APTA report stated: “In the fall of 2023, public transit ridership began to increase again. In September 2023, ridership rose to 74 percent of 2019 levels. In October and November 2023, APTA’s Ridership Trends Dashboard finds that U.S. public transportation ridership has fluctuated between 75 and 77 percent of 2019 levels when comparing the same week in each year.”

Even as the country implemented inconsistent return-to-work policies, these national ridership recovery strides were accomplished, and we still see office occupancy rates that remain around 50 percent, an increase in inflation levels, etc.—all social factors outside our industry’s control that play a factor in reaching or exceeding performance metrics. The following chart from a recent APTA Policy Brief shows the ridership recovery.

In light of those social factors mentioned above, nationally, public transit has been asked to do more with the same level of operational funding that has supported our industry for years. To steal a phrase from Bill Churchill (general manager of County Connection), “Public transit agencies are capital rich but operational poor.” The federal government provides millions of dollars to buy new vehicles, but, until recently, rarely provided funding for the operations. This limits agencies’ ability to expand, increase service frequency, and become a flexible system to meet today’s riders’ needs.

Underfunding of public transit is a nationally recognized issue. Last month, Rep. Hank Johnson (D-GA) introduced legislation in the House that would allocate $20 billion annually for four years to support making the needed operational improvements to transit service. In January, the governors of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania proposed increasing their respective states’ funding by roughly $300 million.

The recently completed, “2023 Study Delegation of San Francisco Bay Area Transit Professionals to Switzerland” Joint Final Report talks about how one country over many years reformed its transit in a complex environment to improve the customer experience and increase ridership—including addressing accountability. “In Switzerland, transit service is plentiful and connects the country’s nine million residents with “clock face” coordinated timetables and integrated fares. Nationwide, travelers complete more than 21 percent of their trips on transit, and more than 50 percent of commuters in the country’s largest cities choose transit, with the 1.6 million residents of the Zurich metro area boasting an amazing 32 percent transit mode share overall.”[1] This is archived through coordinating 260 operators, precisely 37 in Zurich (the San Francisco Bay Area has 27).

However, Switzerland has been able to achieve these service highs because of a few key factors:

- Public transit priority was given over private vehicles—“Switzerland’s trams and buses offer fast, reliable service due to dedicated lanes and signal priority, in combination with other policies that restrict driving in central areas.”[2]

- The Swiss government has invested in capital and operations of transportation agencies based on a coordinated long-range service vision.

- In 1982, a sizable successful measure was passed that focused on increasing investments to meet ridership goals. “National and local transit funding measures have passed consistently since then and have led to higher frequency service throughout the system…”[3]

- Financial investments in public transit have led to voter confidence, which has consistently approved more public investments, equating to a 75 percent increase in service levels in the Zurich region.

- Successful collaboration between the regions and operators.

Back in the U.S., collaboration at a micro level is essential, but to make real strides, collaboration on a macro level will move the needle. That includes cities, counties, transit agencies, and regional planning organizations agreeing on a long-term synced vision if a region’s economic, housing, environmental, and transportation goals are to be met. Most agencies need an active seat at the table to support new land use policies or to be consulted by cities as housing and or economic plans are established. However, we continue to move millions of students, seniors, veterans, and disabled individuals daily across the nation despite fully understanding these outside influence societal factors.

“We’ve built America around cars. If you want to get anywhere in the U.S., unless you live in a downtown area, you need to jump in your car to get there. It’s unsustainable, and it’s not healthy, so we need to figure out a way to move past cars. Doing so will reduce air pollution, reduce greenhouse gases, and also get people walking and biking. And when you take public transportation, it’s a social activity, if you think about it,” says Megan Latshaw, associate professor in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.[4]

Future accountability measures should consider the entire social ecosystem. Housing, lack of job centers, unneeded highway expansion projects, increased crime, work-from-home policies, and increased homelessness are all critical social components that impact how the entire transportation network is effective.

Efficiency should not be confused with effectiveness. Therefore, public transit accountabilities should reflect what we want from transit as a societal result. Historically, accountability measures have been focused on efficiency rather than effectiveness. In today’s world, effectiveness requires a clear vision that more than public transit buys into. Accountability requires each societal pillar to come to the table for the common good and not pitting against each other for political theatre.

We in public transit should embrace this, with the help of our regional partners, to develop these new accountability measures in hopes of provoking sustainable public support to surpass a region’s economic, housing, environmental, and transportation goals.

[1] https://mtc.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=12591847&GUID=8C17916B-F1F9-4598-A336-90389AFFF8DF

[2] https://mtc.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=12591847&GUID=8C17916B-F1F9-4598-A336-90389AFFF8DF

[3] https://mtc.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=12591847&GUID=8C17916B-F1F9-4598-A336-90389AFFF8DF

[4] https://www.planetizen.com/news/2024/01/127199-transportation-access-public-health-issue